《大月恶作剧》指的是 1835 年《纽约太阳报》标题为 “伟大天文发现” 的六篇文章。

【原文】

This article is republished here with permission from The Conversation. This content is shared here because the topic may interest Snopes readers; it does not, however, represent the work of Snopes fact-checkers or editors.

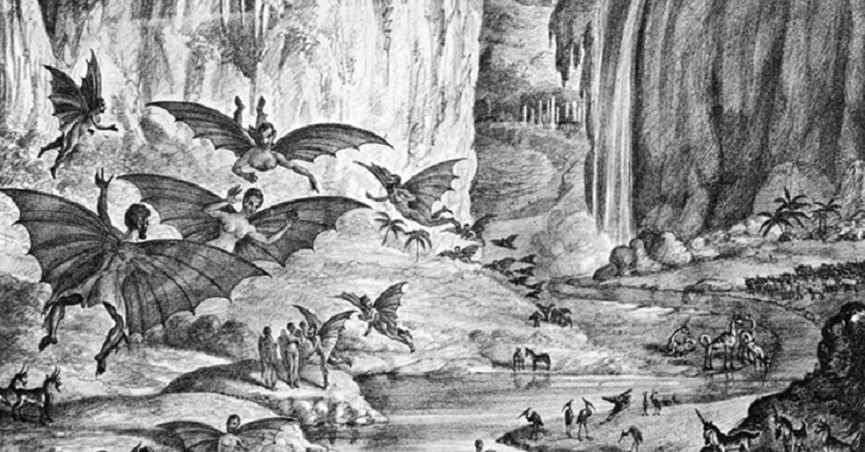

In 16th-century Britain a common saying to describe hoaxing someone was “to make one believe the Moon is made of green cheese”. Absurd, of course. So perhaps people were more credulous by the middle of the 19th century, when a newspaper editor perpetrated what became known as the Great Moon Hoax, persuading gullible readers that on the Moon you could find unicorns and other fantastic beasts.

The Great Moon Hoax refers to six articles in the New York Sun headlined “Great Astronomical Discoveries” and allegedly reprinted from The Edinburgh Journal of Science. Beginning on August 25 1835, they revealed a lunar ecology and civilisation. The hoax tested the parameters of media credibility and “fake news” in the pre-telegraphic age. The stories circulated to other papers around the world.

University of Dundee, Author provided

Though not destroying Dick’s reputation, the hoax challenged his prioritisation of belief over evidence, foreshadowing the fundamental intellectual crises of the mid-Victorian age. Nevertheless, Dick continued to popularise science and democratise access to astronomy. Dundee’s unique public observatory is a bequest from one of Dick’s devotees, John Mills.

Whether or not Dick’s speculations constituted science fiction, they inadvertently midwifed the modern genre through Locke’s parodies. The editor and owner of the New York Herald, James Gordon Bennett, credited Locke with inventing what he called “A New Species of Writing” – “the scientific novel”.

The Dundee Moon Hoax certainly inspired the “lost Scottish father” of American sci-fi, Robert Duncan Milne who grew up in nearby Cupar in the 1840s. His own tales of astronomical discovery bear many similarities to Locke’s lunar utopia. It provided a rich context which shaped Milne’s imagination, driven by creative tensions between scientific secularism, fantastic new technologies and orthodox beliefs.![]()

Keith Williams, Senior Lecturer in English, University of Dundee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.